Tracks

Track |

Time |

Play |

| I. Gan Tzippi | 07:47 | |

| II. Soliloquy | 05:43 | |

| III. King David Dancing Before the Ark | 05:41 |

Liner Notes

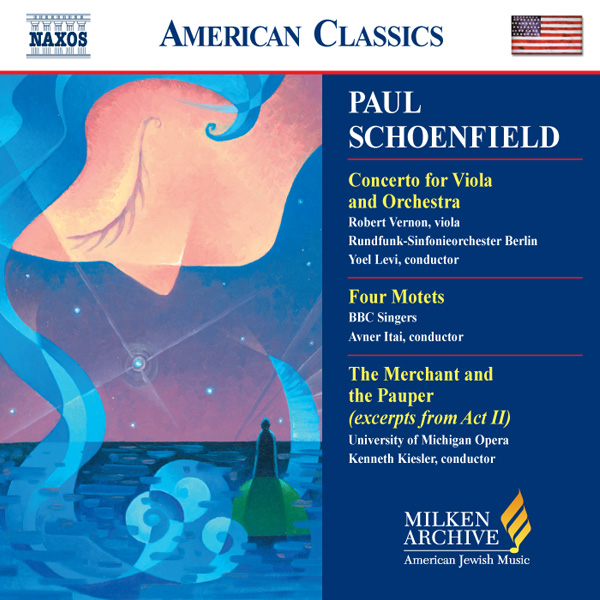

This concerto is emblematic of Schoenfield’s celebrated eclecticism, especially of his ingenious fusion of Western art forms with Israeli and eastern European Jewish popular, folk, and liturgical elements—all within a classical framework. As in much, if not most, of his music, authentic folk motifs are extended and varied, but they are never obscured by his judicious use of such 20th-century idioms as harmonic dissonances, disjunct intervals, and rhythmic complexities. Never superficially superimposed, these techniques are organically employed to give the genuine folk melos freshness and heightened interest.

The concerto was written in 1997–98 expressly for Robert Vernon, principal violist of the Cleveland Orchestra, which commissioned the work and gave it its world premiere with Vernon in 1998. Schoenfield and Vernon were close high school friends in Detroit, and during their student days they frequently played chamber music together. Vernon, particularly moved by the Judaic spiritual character of Ernest Bloch’s Suite Hebraique, has always had an abiding interest in the Judeo-Christian heritage, and he requested that the concerto be “something lyrical and Hebraic.”

Schoenfield composed the concerto mostly in Israel, where he was living at that time. In the basement of the building in which he and his family resided, just beneath his studio, there was a kindergarten called Gan Tzippi (Tzippi’s Garden). Schoenfield became fascinated with the songs he heard the children singing in the schoolroom or in the courtyard just outside, and he determined to base the concerto largely on those tunes. Only later did he learn that some of them were liturgical melodies—a number of them Hassidic in origin—that the children had learned at home or in synagogues; others were apparently common children’s play songs, although some of those may also have had liturgical roots. After the work was completed, Schoenfield explained that he had built the entire piece on fragments of the melodies he had heard from the children. “I just put them together,” he insisted with his characteristic modesty. (Yet the word compose is derived from the Latin componere, “to put together.”)

The concerto is structured with two lyrical movements followed by a furiously driven final virtuoso movement. This is a bit unorthodox, but not revolutionary (Samuel Barber’s Violin Concerto, for example, is similarly ordered). The work does not have a descriptive or programmatic title, but the individual movements do. The first is called Gan Tzippi, after the Israeli kindergarten. It opens with a haunting Lubavitcher Hassidic (ḥabad) melody in the double basses, above which the initial counterpoint in the viola line is derived in part from varied fragments of the same tune. This melody, or niggun (known as niggun l’shabbat v’yom tov), is thought to have been sung by the disciples of the tzemakḥ tzedek—the third rebbe (rabbinical-type leader) of the Lubavitcher Hassidic dynasty (1789–1866). Throughout the movement, this melody is shared by the solo viola and the orchestra, and it is juxtaposed against and interwoven with other tunes or parts of tunes. Some of those, too, exhibit a Hassidic flavor. Most prominent among them is a recurring five-note staccato-like motive. The tempo increases along with the growing melodic intensity, then returns to its slower-paced lyrical character.

The second movement, Soliloquy, is a continuously unfolding, sustained prayerlike meditation, but some of its melodic elements also refer back to the first movement. The third movement, King David Dancing Before the Ark, has a specifically biblical program: the incident in II Samuel: 6, where King David, following one of his military campaigns against the Philistines, has retrieved the Holy Ark from them. David brings the ark back into Jerusalem with enormous joy and public celebration, and he dances without inhibitions “before the Lord with all his might.” But when his wife, Michal (daughter of the former King Saul), sees him “leaping and dancing” in front of the common people and even the servants at the expense of his royal dignity, she is put off (“and she despised him in her heart”). She admonishes him for what she deems such inappropriate behavior, asking him how the King of Israel could have earned honor and respect by “uncovering himself [to dance]” shamelessly, especially in the presence of “handmaids of his servants,” like an ordinary, vulgar man. David replies defiantly that it was “before the Lord” that he danced and celebrated, and that he will continue to do so—even more so: “I will be yet more vulgar than this.”

Schoenfield characterized this third movement as a “programmatic description of a king letting the ecstasy in his character shine through.” The ecstatic dancing and fervor are depicted by a constant motoric interplay among several folk-type melodies and among phrases and motives extracted from them. Michal’s scolding is represented by a trombone—which one reviewer thought “suggests she is an irksome figure indeed.” Free syncopations in the solo viola mirror King David’s defiance and dismissal of her criticism. Many of the tune fragments in both the first and second movements again figure prominently in this finale, giving the entire work an overall unity.

“The viola is by nature a reflective instrument,” Schoenfield declared during the rehearsals for the premiere. Not exclusively, however, if one judges from this third movement. Schoenfield has lifted the instrument completely out of that mode and treated it here as a highly virtuoso vehicle—appearing to dance as exuberantly as did King David. This movement makes considerable technical demands on the violist and exploits the instrument’s higher registers. It is also rich in generic inflections and gestures associated with so-called klezmer music—the styles and sonorities typical of 19th-century eastern European Jewish wedding and street bands. Several recognizable Hassidic and other eastern European Jewish folk melodies stand out in this finale. The opening one is a familiar incipit motif of many folksongs and dance tunes. Another is a Lubavitcher Hassidic version of a verse from Deuteronomy (16:14), v’samaḥta...(And you shall rejoice...).

Credits

Composer: Paul SchoenfieldPerformers: Yoel Levi, Conductor; Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin; Robert Vernon, Viola

Publisher: Migdal Publishing

Coproduction with DeutschlandRadio and the ROC Berlin-GmbH