Tracks

Liner Notes

In the popular imagination of the 20th and 21st centuries, the very name Masada has become a dramatic, unorthodox, or even ironic symbol for Jewish national defiance in the face of overwhelming enemy military superiority and even inevitable defeat. The most commonly accepted narrative account of the national as well as human tragedy believed to have occurred there in 73 C.E—whether embellished narrative, accumulated myth, faithful chronicle, or a bit of each—has also come to serve as an important political and historical anchor of collective memory for both renewed Jewish national consciousness and, more directly, for the modern State of Israel and its sense of historical continuity and national roots.

Masada is an imposing and isolated plateau, towering above the Dead Sea and the Dead Sea valley at the edge of the Judean desert, upon which, in antiquity, stood a fortress. It was first fortified by the Jewish high priest Jonathan in the 2nd century B.C.E., and it was later the site of King Herod’s royal palace, citadel, and fortifications, built at the end of the 1st century B.C.E. as a refuge and defensive post—in response to the perceived dual threat from Jewish political rivals in Jerusalem and from Queen Cleopatra of Egypt. It has been assumed that a Roman garrison was most likely stationed on Masada from 6 until 66 C.E., when the Jewish Wars (66–70/73) began and the initial attack against the Romans was launched from there; and when, according to the contemporaneous Jewish historian Josephus, a band of Zealots under Menahem ben Yehuda of Galilee took it from the Romans. Subsequently, following the fall of Jerusalem in 70 C.E., Masada became the final, doomed fortified outpost of the Sicarii—a radical fringe sect of Jewish rebels or self-styled resistance fighters who previously had killed 700 Jewish women and children at En Gedi during a raid for supplies—and a refuge for those who faced capture, including entire families. Whether the Sicarii (sikarikim), with whom the Masada residents were affiliated at the time of its fall, were the same group as those identified as the Zealots (kana’im), as is often loosely assumed, or whether the two were distinct, perhaps rival extremist sects, is uncertain according to some opinions. But most contemporary historians espouse the latter view. After Menahem’s murder in Jerusalem by his rivals, Elazar ben Yair of Galilee became the leader of the Masada-based rebels and residents, and he remained so until their defeat.

Having conquered the two other holdouts—Herodium and Macherus—the Roman forces laid siege to Masada and prepared to storm its defenses and permanently crush all lingering vestiges of resistance. Prior to the modern usage of the name (metzada), it appeared only in Greek transcription. It has been suggested that it might have been an Aramaic form of the word metzad (stronghold).

Our only contemporaneous description of Masada’s fall was furnished by Josephus in a work titled The Jewish Wars. By the time of the Masada siege, Josephus, who was previously a commander of the Jewish army in the Galilee, had already surrendered personally to the Romans following Vespasian’s conquest of some principal Galilean positions. Thereafter, secure on the Roman side, he devoted himself to historical writings, which include a detailed account of the Jewish revolt from 66 until its end in 73.

According to his own description, however, Josephus surrendered only after a small group of his comrades had decided upon collective suicide while trapped in a cave in the Galilee hiding from the Romans—and after he had persuaded them to draw lots to determine who would kill whom—foreshadowing the scene he later described with reference to Masada. By his own admission, as one of the last two men alive, he saved himself by convincing the other remaining man that the two of them should surrender. Some have suggested that this was a betrayal of his fellow rebels. What his motives, if any, might have been, whether his self-described role in that episode might have colored his later account of the fall of Masada, or whether in fact that incident at Jotapata actually occurred in the way he related it, are all matters of speculation. However, the very account of the Jotapata suicide has been challenged in terms of plausibility and is generally considered highly suspect.

Josephus relates that the Roman army under Flavius Silva began its campaign against Masada in 72 C.E. with the Tenth Roman Legion and auxiliary troops—estimated at between 8,000 and 10,000 strong—together with several thousand Jewish slaves or war prisoners. After a protracted siege, they breached the walls of the fortress only to find that the Jews had built a second wall, which the Romans set on fire. In the Josephus narrative, the Romans then halted and prepared for their final attack the next day, by which time any hope of success in further resistance appeared futile, and the specter of either slaughter or slavery hung over the populace. However, citing both archaeological evidence and the logic of military strategy to the contrary, historian Shaye Cohen has questioned the truth about the Roman army’s pause, at the same time observing that this purported postponement of their final attack provided Josephus his necessary window of opportunity for the creation of Elazar’s speeches and the deliberations about the communal suicide.

According to the Josephus account, fortified by its ingrained status as national legend, Elazar ben Yair proposed “collective suicide” to the entire community as a more honorable and defiant option, which would deprive the Romans of complete satisfaction in their imminent victory. He suggested that the men first kill their wives and children, and then themselves, rather than be taken prisoners. Josephus claims to quote (or paraphrase)—but probably he invented, for both literary and political purposes—Elazar’s now famous speech (the first of two), in which he reminds the people that they had long ago “resolved never to be servants to the Romans, nor to any other than to God,” the time now having arrived to “make that resolution real in practice.” He exhorts them to “die bravely and [while still] in a state of freedom.” The Josephus account unfolds with the men accepting Elazar’s solution (after some initial objections followed by further persuasion), slaying their wives and children after embracing them tearfully, and then casting lots to determine the ten men who would kill the rest. The last man then set fire to the palace and other buildings and fell on his sword. Thus, when the Roman army entered the fortress, it found 960 dead bodies. However, two women and five children, who are said to have relayed the story, hid in a cave and survived, later to be found by Roman soldiers.

Even apart from the issue of the veracity of the Josephus account or its modern acceptability as an exemplary national legend, in theory there was, of course, yet another defiant—though still ultimately suicidal—alternative: fighting to the last man (and perhaps even the last woman), accepting the inevitability of total defeat and death, but taking as many enemy lives as possible in the process (a course followed on some occasions by Jewish resistance fighters against the Germans during the Second World War). In some modern ex post facto interpretations, that might be viewed as the more heroic choice—and therefore the less tragic one—and from a religious or religious-legal perspective, it could have avoided the issue of suicide, forbidden in Jewish law. On the other hand, a pitched battle would almost certainly have resulted in the enslavement of a significant number of Jews and perhaps a worse fate for the women. In that case, the deaths, whether self-inflicted or suicide by acquiescence in homicide, might be considered as dying al kiddush hashem (for the sanctification of God’s name)—i.e., Jewish martyrdom—the more so if it was assumed that forced commission of the most serious capital transgressions would have followed surrender or capture. Yet the more traditional legal view regarding martyrdom involves allowing oneself to be killed rather than taking one’s own life in advance. In any case, whether national pride and dignity (which would not in themselves justify suicide in Jewish law), or religious devotion, or simply fear of the physical consequences of capture was the prime motivating force behind the episode is only one of the issues at the core of modern reexamination of the Masada story. That question concerns not only religious parameters, but also the appropriateness of Masada’s adoption as a historical symbol and Jewish national metaphor. This is but one of the several subjects of debate concerning Masada and its significance.

Although the writings of Josephus contain the only account from that time frame and the only discussion for many centuries afterward (Masada is not even mentioned in the Talmud, and Roman sources such as Pliny refer to it only in passing), the anonymous medieval historical work the Book of Yossipon (circa 10th c.) apparently drew from Josephus in its reference to Masada. In that version of the narrative, after killing their wives and children, the men do not directly take their own lives, but rather all die (still in a sense suicidally) fighting Roman soldiers in a final battle. But that version is not generally accepted either—certainly not in its entirety. Most historians, archaeologists, and other scholars, especially in the absence of any other contemporaneous reports, do now accept a portion of the Josephus account as basically, if only partially, historical, in the sense that a communal suicide (though probably not involving the entire population) most likely did occur roughly along the lines he relates. But it is now also obvious that he embellished, exaggerated, and altered the account to suit both literary effect and political agendas. The archaeological excavations have been held to validate that position, notwithstanding the variety of views concerning the historical interpretation or political-social uses of the story.

Shaye Cohen has proposed motives for Josephus’ invention of “additional” aspects, suggesting that Josephus wanted, through Elazar’s speech, to discourage further rebellion against Rome and that he therefore wanted Jewish readers of his chronicle to “realize that the way of the Sicarii is the way of death” and to find Elazar admitting in his speeches that his policies of resistance had been wrong—that the rebels could not prevail. Cohen also concludes, while acknowledging a collective suicide by at least some of the Sicarii, that “the use of lots as described by Josephus must be fictitious too.” Based on all available evidence, Cohen has conjectured (admittedly) that some Jews did kill their families as the Roman army was breaking through the wall (since he is convinced that the pause never occurred), some Jews killed themselves after destroying as much as possible, some tried unsuccessfully to hide or escape, some did fight to their end, and the Romans, rather than take prisoners, probably killed any remaining Jews.

Although subsequent medieval incidents of communal suicide as religious martyrdom are well known in European history, the Masada episode—whatever its interpretation—at most remained marginal to collective Jewish consciousness until well into the modern era, which gave birth to the first serious secular scholarly attention to Jewish history. (The works of Josephus were not translated into Hebrew until 1862.) Before then, to the extent that there was any awareness of Masada at all, it related to the incident as a symbol of Jewish suffering rather than one of national struggle. It was not until the maturity of the Zionist movement and the rejuvenation in Jewish Palestine following the First World War, and then the gaining of statehood, that Masada came to constitute an important part of national lore and historical “rediscovery.”

Increased general Jewish awareness of Masada, especially among Zionist-oriented circles and in Palestine, was generated by Yitzḥak Lamdan’s epic Hebrew poem of the same name (Metzada), published in 1927, which quickly became popular and contributed to the story’s elevation to national folkloric status. Even as late as the 1970s it was only natural for Marvin David Levy to turn to it as one of his chief sources for the text of his musical work.

The actual site of Masada was identified geographically for the first time in 1838 by two American explorers, followed by investigations, visits, and surveys by others in succeeding decades and into the first half of the 20th century. Their interest, however, lay more in Roman than in Jewish history, and in archaeology per se rather than in historical-political issues of Jewish sovereignty and its roots in antiquity. Israeli archaeologists began work in the 1950s and arrived at some important findings, but these became preliminary stages to the highly publicized watershed excavation and reconstruction conducted in 1963–65 by Israeli archaeologist Yigal Yadin. That expedition involved, in addition to a team of professional archaeologists, thousands of volunteers from many countries, which lent an ideological and even idealistic air to the project and ultimately helped reinforce Masada’s position in Jewish national—hence Israeli—history as a symbol of defiance and patriotic continuity. The expedition and its results, followed by widespread attention, international traveling exhibitions, and extensive new media coverage, firmly established and reconfirmed Masada not only as a significant pilgrimage point—a function it had already begun to serve for dedicated Zionists and youth movements since the waning days of the Ottoman Empire, and for Israelis even before the Yadin excavation—but now as a major international tourist attraction. Thereafter Masada inspired artistic creations, historical and photographic books, novels, films, television programs, documentaries, and musical works. Especially in the euphoric post-1967 days following the Six Day War and during the early 1970s, it was an obvious subject for any composer seeking to address an Israel-related topic. Notwithstanding several other worthy compositions based on this story, Levy’s cantata and the opera Masada by Israeli composer Joseph Tal probably stand as the two most sophisticated musical treatments to date.

Perhaps more problematic for our understanding of Masada than the validity of the Josephus account or his motives are the complex questions that fuel varying historical, religious, and political interpretations of this episode vis-á-vis its place in collective memory. Apart from the question of whether the 960 deaths can properly be considered “collective suicide” as opposed to accepted homicide (and whether the men had the moral right to make that decision for the women and children, even if they did not resist), does Masada symbolize national heroism or religious martyrdom?

Was the suicide an act of courage or fear? To what extent does the incident represent communal death as an ultimate defeat, and conversely, to what extent was it a denial of total victory to the enemy—and in that sense some measure of Jewish victory in succeeding to die with dignity as free people? Is Masada an appropriate narrative for either modern Jewry or modern Israel in establishing ancient precedence for national legitimacy and roots? Should it be viewed as a paradigm for Jewish national resistance and tenacity or as a symbol of Jewish suffering? In her book Recovered Roots: Collective Memory and the Making of Israeli National Tradition, Israeli historian Yael Zarubavel sums up a possible answer as follows:

The activist and the tragic commemorative narratives of Masada coexist in contemporary Israeli culture and are called upon in different situations. Masada thus continues to be a historical metaphor of active resistance and renewal in some instances and a historical metaphor of persecution, death, and suicide in others.

These are only a few of the questions triggered by objective consideration of what happened—or what did not—on Masada in the year 73, and of what Masada has come to represent to the world. Zarubavel’s observations offer some keen insights, which contribute toward reconciling some of the conflicting prisms through which the episode can be refracted:

The commemorative narrative plays up the defenders’ readiness to die as an ultimate expression of their patriotic devotion and highlights it as the core of their exemplary behavior. But it plays down or ignores the particular mode of death they chose. In this context the suicide becomes a marginal fact, a small detail within the larger picture of an “active struggle” for national liberation.

Levy’s cantata both commemorates the heroic parameters of Jewish defiance and mourns the tragedy of the communal deaths with its recitation of the “mourners’ kaddish.” Yet his overall conception seems to emphasize the former over the latter, Jewish strength over weakness, especially in the dramatic final pronouncement by the chorus: “Never again!”

Marie Syrkin has explained this apparent contradiction in her article “The Paradox of Masada” (coincidentally published in the same year as Levy completed his work), which is also quoted by Zarubavel:

Though the outcome of the struggle at Masada was the suicide of its last defenders, only the heroic resistance of which it was the scene has registered in the mind of Israel, not the grim “un-Jewish” finale. However illogically, what happened at Masada permeates the imagination of Israel as the ultimate expression of active struggle, the reverse of an acceptance of death.

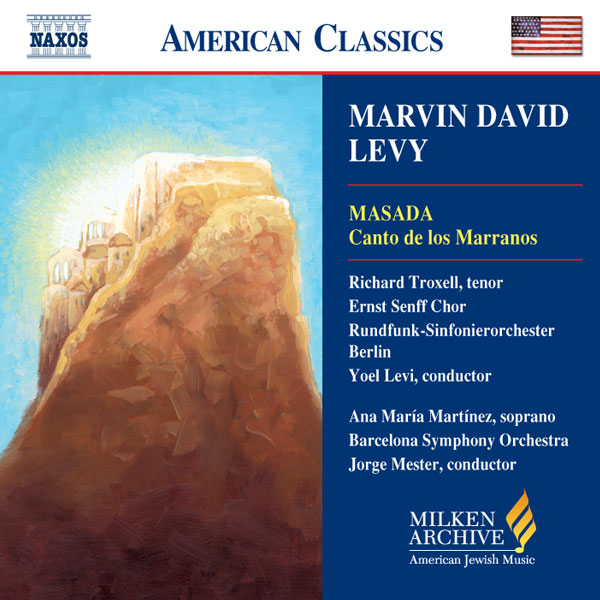

Levy’s Masada was originally commissioned by the National Symphony Orchestra as a musical-dramatic work expressly for the legendary American tenor Richard Tucker. Like most American Jews at that time, Levy was not yet familiar with the Masada episode or its place in Jewish history, and the 1963–65 dig in Israel had just begun to generate substantial general public awareness and interest. While searching for a subject for the commissioned work, he coincidentally saw the traveling exhibition of Yadin’s archaeological excavation and reconstruction, then on tour at the Jewish Museum in New York. Instantly impressed by the dramatic possibilities of the Masada story, Levy determined to base his new piece on it as a full-length oratorio with a narrative speaking role as well. “Whether completely true or partially fabricated [by Josephus],” he later recalled, “I realized immediately that there was a story there for musical expression.” Levy then did considerable research, and he eventually based his text in large part on the Lamdan poem as well as on the writings of Josephus. In Elazar ben Yair’s purported speech he saw “the big tenor moment—right there!” and later described it as the “lynchpin of the work.”

Levy’s original version of Masada received its premiere in 1973 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., with Tucker in the tenor role and world-renowned bass George London (then retired from singing) narrating, and the National Symphony Orchestra and the University of Maryland Chorus conducted by Antal Dorati. “But I never really finished the work—it was performed, so it was finished after a fashion,” Levy later said. He subsequently revised it—rewriting some sections and adding the mourners’ kaddish at the end as an extension—for a performance in 1987 with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Margaret Hillis.

This recording represents yet a third version of the work, which Levy rewrote for the Milken Archive—this time as a shorter cantata without a speaking part. It contains both new texts and fresh musical material.

Lyrics

Sung in English and Hebrew

PART I

CHORUS:

yitgaddal v’yitkaddash sh’me rabba

b’alma div’ra khirute

v’yamlikh malkhute

b’ḥayyeikhon uv’yomeikhon

uv’ḥayyei d’khol beit yisra’el

ba’agala uvizman kariv

v’imru: amen

[May God’s great name be even more exalted and sanctified in the world that He created according to His own will; and may He fully establish

His kingdom in your lifetime, in your own days, and in the life of all those of the House of Israel—soon, indeed without delay. (Those praying here signal assent and say “amen.”)]

ELAZAR BEN YA'IR:

The War of the Jews against the Romans began more than one hundred thirty years ago. Battles broke out from time to time, but now Emperor Titus has had enough of our rebellion, and he has put an end to it. Rome rules the world, and we are its greatest conquest. And so Jerusalem has fallen.

CHORUS:

Jerusalem has fallen. The Temple is destroyed.

y’he sh’me rabba m’varakh l’alam ul’almei almaya

[May His great name be praised forever, for all time, for all eternity.]

ELAZAR:

The Temple is destroyed. Enough to quench the flames that engulf it,

the whole city runs with blood.

CHORUS:

The whole city runs with blood.

yitbarakh v’yishtabbah v’yitpa’ar v’yitromam

v’yitnasse v’yithaddar v’yitalle v’yithallal

sh’me d’kud’sha

[Blessed, praised, glorified, exalted, elevated, adored, uplifted, and acclaimed be the name of the Holy One.]

ELAZAR:

The Romans fall over the dead they have slaughtered in the streets.

CHORUS:

b’rikh hu

l’ella min kol birkhata v’shirata

tushb’hata v’nehemata da’amiran b’alma

v’imru: amen.

[Blessed be He—over and beyond all the words of blessing and song, praise and consolation ever before uttered in this world.

(Those praying here signal assent and say “amen.”)]

ELAZAR:

Caesar ordered some of the captured to be put in bonds and sent to the Egyptian mines, others sent to the provinces where they might be run through by swords or torn apart by wild beasts. The rest have been sold as slaves. Still, my band of Zealots, near a thousand strong, survives.

CHORUS:

Elazar ben Ya’ir, those of us not murdered or imprisoned are still your devout followers. We, your loyal Zealots, led this last revolt against the Romans. Now you see a fallen, conquered people before you. We await the footsteps of the end. See our hands, the first to raise the flags of every gospel and the last to receive comfort. Our hands are stretched out before you. Take them and lead us to a place of refuge.

ELAZAR:

God give me the strength of my father. Help me to find a way.

CHORUS:

Elazar ben Ya’ir, we can still escape with our wives and children.

ELAZAR:

y’he sh’lama rabba min sh’mayya

v’ḥayyim aleinu v’al kol yisra’el

v’imru: amen.

[May there be abundant peace for us and for all Israel. (Those praying here signal assent and say “amen.”)]

CHORUS:

Help us find a way.

ELAZAR & CHORUS:

ose shalom bimromav

hu ya’ase shalom aleinu v’al kol yisra’el

v’imru: amen.

[May He who establishes peace in His high place establish peace for us and for all Israel. (Those praying here signal assent and say “amen.”)]

ELAZAR:

To the south of Jerusalem, south of Jericho, south of En-gedi in the Dead Sea valley, there in the Wilderness of Judea, alone, in isolation, suddenly rises the mountain plateau of Masada.

CHORUS:

Masada!

ELAZAR:

Masada, the palace stronghold built by Herod the Great. He thought himself “King of the Jews” and crucified pretenders. Fearing continued rebellion from his people, he fortified the royal citadel of Masada; he built huge cisterns to store rainwater, and amassed provisions. He encircled the summit with a stone wall. His court could then retreat there, defend and sustain themselves for years if necessary.

CHORUS:

The Romans remember the fortress atop Masada. They were garrisoned there after Herod’s death, until four years ago, when other patriots drove them out. The Romans remember the access to the mountaintop is only by a single steep and narrow path. No armed legions can ascend together. They can only reach it by climbing one at a time. So it can be defended by even our small numbers, and used as a base for raiding operations.

ELAZAR:

There we can join our fellow fighters against oppression. It may be the last point of Zealot resistance.

CHORUS:

Our last stand!

ELAZAR:

Then follow me, children of Masada. Let us ascend the wall. Let us dance with joy for one more chance to fight for freedom!

CHORUS:

The chain is still not broken, from father to child, from fire to fire, the chain continues. Thus danced our fathers, one hand on a neighbor’s shoulder, the other holding a scroll of the law. A people’s burden is raised with love. So let us dance, one hand gripping the circle, the other clutching our heavy book of sorrow, so let us dance. When our fathers danced, they closed their eyes and wells of joy were opened. They knew they were dancing on the abyss, that if they opened their eyes, the wells of joy would turn dry. So let us dance too, with our eyes closed. Thus shall we continue the chain, lest it crumble into the deep, so let us dance too.

ELAZAR:

To the south of Jerusalem. (CHORUS: Onward!)

South of Jericho! (CHORUS: Onward!)

South of En Gedi! (CHORUS: Onward!)

To the shores of the Dead Sea!

CHORUS:

Let us continue the chain! Surely we have grown big and tall! Smiting our heads against the heavens, the dance of Masada thunders in the ears of the world! Make the suns drums! Make the stars cymbals! Thus is the victory of Masada foretold beneath the heavens! O world, bend your head to our redeeming dance. God with us in the circle will sing: Israel!

ELAZAR:

Who is kneeling? Who has fallen? A tired brother? Why do you cry, child of Masada? Arise! Weep not for broken yesterdays. We have tomorrow!

CHORUS:

We have tomorrow!

ELAZAR:

And if Fate says to us, “In vain!”

CHORUS:

We shall pluck out its tongue!

ELAZAR:

And in spite of itself, in spite of its laughter, defeated, Fate shall nod its head.

ELAZAR & CHORUS:

Indeed. Amen! Amen!

PART II

CHORUS:

Three years have passed. We have defended ourselves. There are some fifteen thousand Roman legionnaires, led by Roman General Flavius Silva, stationed down at the foot of Masada, but they have not been able to breach our defense. They have surrounded the base of the mountain with a high wall, leaving us no escape. They have built an assault ramp to the top. And now they have moved the battering ram up directly against our wall. Though every day we raid the camps below, we know theirs will be the final victory.

ELAZAR:

Great is their pain, and who can tell if it will not become greater, grow—become more righteous than this distant charity for which they sin? As tender, upright trees, they have set themselves here, but under the iron of Masada’s heavens, on the brass of her earth, they wilt day after day. As autumn leaves, they drop from their twigs, and no one knows where the winds carry them, if they may bring another branch to flower, no one knows.

CHORUS:

Look out there, in the darkness, someone is coming from outside the camp. Look, suddenly shining, the dying campfires move, and an unseen hand again binds crowns of flame to them. And by their light above the mountain of Masada a figure appears. He has an afflicted smile, a comforting look, and the majesty of might. Who watches us so? Who smiles? Who is this wondrous person? Elazar ben Ya’ir.

ELAZAR:

O God, my God, God of Masada, I have waited, trembling, for a miracle.

Now our enemies rage at our gates. You have sent us the final trial.

You have also sent me the understanding of what You ask from us.

Then one great mercy: give us the courage to do what must be done to redeem ourselves, so that if we are here today before You, tomorrow

Your eyes will shine upon us when we are not.

CHORUS:

Lord, be near us when You bring us out of this world. Bring us in peace to the life of the world to come. By those who hallow You, be sanctified; by those who exalt You, be glorified; by those who love You, be blessed.

ELAZAR:

My loyal followers, daybreak will end our resistance. But we are free to choose a noble death with our loved ones—an honorable death by our own hands. It will be easier to bear. And our enemies cannot prevent this, however they may pray to take us alive. Let our wives die unabused, our children without the knowledge of slavery, by doing each other the final ungrudging kindness, preserving our freedom as a glorious beacon of light. First let the whole fortress and all our possessions go up in flames. It will be a bitter blow to the Romans to find that we are beyond their reach. Only one thing let us spare—our store of food. It will bear witness that we perished not through want, but because, as we resolved from the beginning, we choose death rather than slavery, a death for which we shall live forever.

CHORUS:

We choose death to keep that dream alive!

ELAZAR:

As of now, a new Book of Genesis is opened on the wall. And like our fathers, upon finishing the Torah before starting it again, let us roar with a new and last roar of the beginning! Be strong, be strong, and we shall be strengthened!

CHORUS:

shenit m’tzada, lo tipol!

am yisra’el ḥai.

[Masada will never fall again!]

ELAZAR & CHORUS:

Never again shall Masada fall!

Am yisra’el ḥai!

[May Israel live!]

CHORUS:

O Lord our God, and God of our fathers, we sanctify Your name on earth as it is sanctified in heaven. Bless us, all of us together, with the light of Your presence, for by that light You have given us the Torah of life, Your sacred law. Holy are You and holy is Your name.

ELAZAR:

kaddosh kaddosh, kaddosh adonai tz’va’ot,

m’lo khol ha’aretz k’vodo.

[Holy holy, holy is the Lord of Hosts, the whole earth is full of His glory.]

CHORUS:

You have drawn us near and called us by Your great and holy name.

We entrust our lives into Your loving hand. Our souls are ever in Your charge. O Lord our God and God of our fathers, who call the dead to life everlasting, remember us unto life.

ELAZAR:

y’varekh’kha adonai v’yishm’rekha.

[May the Lord bless you and keep you.]

CHORUS:

ken y’hi ratzon.

[So may it be His will.]

ELAZAR:

ya’er adonai panav elekha viḥuneka.

[May the Lord make His countenance to shine upon you and be gracious unto you.]

CHORUS:

ken y’hi ratzon

[So may it be His will.]

ELAZAR:

yissa adonai panav elekha v’yasem l’kha shalom.

[May the Lord turn His countenance unto you and give you peace.]

CHORUS:

ken y’hi ratzon

[So may it be His will.]

ELAZAR:

v’imru: amen.

[Now respond: Amen.]

CHORUS:

Amen

ELAZAR & CHORUS:

Amen

CHORUS:

May the Lord make His countenance to shine upon you and be gracious unto you.

ELAZAR:

May the Lord turn His countenance to you.

CHORUS:

And give you peace. So may it be His will.

ELAZAR:

So may it be His will.

CHORUS:

Never again!

ELAZAR & CHORUS:

Amen. Amen. Amen.

Credits

Composer: Marvin LevyPerformers: Ernst Senff Choir, Sigurd Brauns, chorus master; Yoel Levi, Conductor; Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin; Richard Troxell, Tenor