Tracks

Track |

Time |

Play |

| Narration | 01:40 | |

| Ma nishtano - The Exodus | 05:12 | |

| Gebensht - Chorale | 01:08 | |

| Riboino shel oilom | 03:50 | |

| Narration | 00:21 | |

| Linder april - A mild April | 03:44 | |

| Vet kumen? (Will He Come?) | 01:09 | |

| Vet kumen? (continued) | 01:09 | |

| Narration | 00:14 | |

| Un oib s'vet nor a minyen farblaiben | 01:55 | |

| Di shlacht - The Battle | 00:34 | |

| Zei zenen gekumen - They Came | 04:23 | |

| Narration | 00:31 | |

| Dos Yingle (The Boy) | 02:12 | |

| Narration | 00:26 | |

| Di fon - The Banner | 04:04 | |

| Der Toyt | 04:32 | |

| Narration | 00:24 | |

| Shfoykh khamoskho | 01:52 | |

| Narration | 00:27 | |

| Rum un gevure | 02:29 | |

| Narration | 00:31 | |

| Aza der gebotiz | 04:53 |

Liner Notes

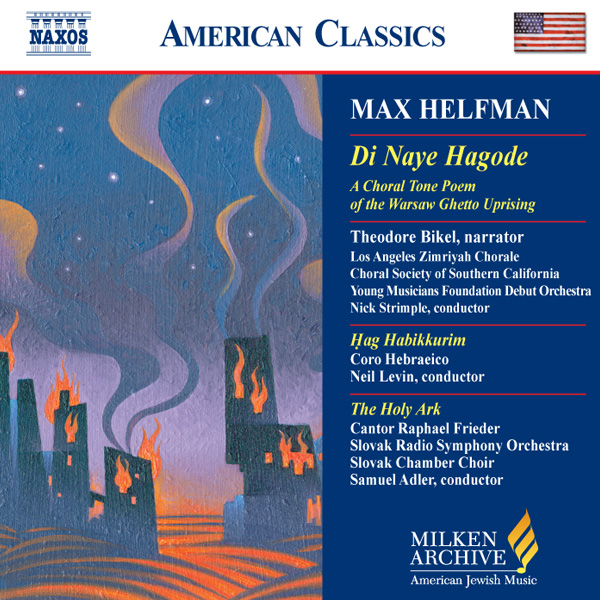

Di naye hagode (The New Haggada, or The New Narrative) is a dramatic choral tone poem–cantata based on Itzik Fefer’s epic Yiddish poem about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising—Di shotns fun varshever geto (The Shadows of the Warsaw Ghetto). The term haggada, which translates generically as “narrative,” is most commonly associated with the specific fixed narrative that is recited and reenacted at the Passover seder—the annual home ritual in which the ancient Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, their liberation from bondage, and their embarkation on the path to a new, independent national as well as religious identity are recounted and celebrated. Helfman, who is presumed to have adapted Fefer’s words for his choral texts as well as for the English narration, took the title from the multiple appearances of this phrase within the poem. The hagode reference gave the piece a heightened historical and moral significance—not only because the uprising and the Germans’ final liquidation of the ghetto occurred during Passover, in 1943, but also because liberation, national survival, and, especially, the impetus for remembrance and undiluted recollection acquired a new and even more immediate meaning for the Jewish people in the post-Holocaust world. Just as all Jews are required annually to recall and relive the events of the exodus from Egypt, and just as they are obligated to transmit the story to their children in each generation, so did Fefer exhort his people to tell this story—if for no other reason than perpetually to pay homage to the brutally murdered Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto who died with the collective honor of resistance: “Forever blessed are they who remember the graves....And whoever does not maintain the wrath [against the Jews’ murderers] shall be forever cursed.”

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

There were nearly 400,000 known Jewish residents of Warsaw—about a third of the city’s overall population—when the German army entered the city on September 29, 1939, following its invasion of Poland on the first of that month. (Some estimates place the numbers even higher, to include those who had concealed or abandoned their identities.) Even before the Germans began to construct the ghetto and commence deportation and murder, they segregated the Jewish population by requiring identifying armbands, marking Jewish-owned businesses, and prohibiting Jews from using public transport. Forced labor and confiscation of Jewish property followed soon after. In April 1940 the Germans began constructing a wall that, by the following October, would enclose the established ghetto into which all Warsaw Jews (and those whom the Germans perceived as Jews) and Jewish refugees from other provinces were required to reside. Initially, about 400,000 Jews were forced into the ghetto, and by July 1942 its population is estimated to have grown to half a million. Intense overcrowding left thousands of families homeless, starvation and disease were rampant, and child beggars and smugglers roamed the streets. Leaving the ghetto without permission was punishable by death. By the summer of 1942, more than 100,000 Jews are believed to have died within the ghetto itself, in addition to many thousands of others who had already been deported and subsequently murdered in slave labor camps—all prior to the outright deportations to actual death camps for wholesale annihilation.

A number of groups within the ghetto were involved in the active resistance. The most prominent of these were the Zionist organizations that represented various shades of nationalist political philosophy, along with the General Jewish Workers’ Union (the Bund) and the smaller, communist-leaning Spartakus. Political underground groups in the ghetto secretly disseminated information on German plans and strategies. They documented events for posterity; issued clandestine periodicals in Hebrew, Yiddish, and Polish; and prepared for armed resistance. The first underground Jewish paramilitary organization, Swit, was formed in Warsaw as early as December 1939, even before the construction of the ghetto, by Jewish veterans of the Polish army, most of whom were Revisionist Zionists. In 1942 a second underground militant organization was formed by a coalition of four Zionist groups together with the communists. The Bund formed its own fighting organization, Sama Obrona (Self Defense), but when the mass deportations to the Treblinka death camp began, in July 1942, none of those resistance groups had yet succeeded in acquiring arms.

The president of the Judenrat (the Jewish council in each German-created ghetto that was established to organize, regulate, and administer life therein and to carry out German directives), Adam Czerniakow, committed suicide rather than accede to the German orders to cooperate in the deportations. His successor, however, did obey the German orders. (Although the Judenrats and their presidents have often been condemned as collaborators—operating, at best, under self-made delusions that resistance was futile and that their acquiescence could buy time to save at least some people—the entire episode is as complex as it is painful to confront. Some council members were convinced that they had no alternative, and there is also evidence that some of them secretly assisted resistance groups.) The number of deportees ranged from 5,000 to 13,000 daily. By September 1942, the combined number of Jews who had either been murdered in the ghetto or deported to Treblinka is estimated at 300,000—out of about 370,000 residents prior to the commencement of those deportations less than two months earlier. After that, the Germans restricted the number of remaining ghetto inhabitants to 35,000.

The leaders of several Jewish underground movements then created the combined Jewish fighting organization known as Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa—ZOB—to resist further deportations. By that time, the Germans’ genocidal intentions (as opposed to harsh wartime measures or casualties) were exposed—no longer exaggerations or rumors—since a few escaped Treblinka inmates had managed secretly to return with the news of the planned full-scale annihilation. As 1942 drew to a close, the ZOB, joined by the Bund, scrambled to intensify preparations for armed resistance. Some weapons were smuggled into the ghetto with the aid of Polish underground organizations on the outside; other arms were acquired on the black market. Homemade firearms were also manufactured in secret underground workshops, and bunkers and tunnels were created.

When the Germans reentered the ghetto in January 1943 for their next round of deportations and for its eventual liquidation, they encountered unanticipated armed resistance. They succeeded in destroying the hospital and shooting its patients, and they deported everyone in the hospital and many other ghetto residents. But this time the underground organizations succeeded in forcing the German units into four days of intensive street fighting. Eager to avoid the potential contagion and encouragement that might result in similar resistance among cordoned Jewish populations elsewhere under German occupation—and throughout Poland—once word would reach them of the spirit of the Warsaw Ghetto fighters, the Germans temporarily retreated to a tentative suspension of the deportations, relying instead on the trickery of “voluntary” recruitment for putative labor camps. During that period, about 6,000 additional Jews were sent to Treblinka nonetheless, and about 1,000 more were murdered within the ghetto.

Despite the short-lived cessation of physically forced deportations, life within the ghetto was all but frozen. Unauthorized Jewish presence in the streets was forbidden, punishable by death. The ZOB, along with the other underground Jewish organizations (twenty-two fighting units in all), continued to prepare for further armed resistance in anticipation of the Germans’ inevitable return. The moment arrived on April 19, 1943, on Passover, when the Germans—this time prepared with armored vehicles as well as artillery—moved in for a final assault. At first they were repulsed, even suffering casualties. When they resumed their advance—only to fail to prevail in the open street engagements—they set fire to the houses, block by block. Large numbers of Jews were burned to death, while many of those hiding in the bunkers met their end by grenade and gas attacks. The Jewish underground forces continued on the offensive, attacking German units at every opportunity, until the ZOB headquarters fell to the Germans on May 8, 1943, in a battle that took the lives of at least 100 Jewish fighters. Eight days later, General Jurgen Stroop, who had changed his name in 1941 from Joseph to be perceived as “more Aryan” and who had commanded the so-named “Great Operation” (Grossaction) since April 19, reported the successful and complete liquidation of the ghetto. To mark his victory, the grand synagogue on Tłomackie Street was blown up and leveled. This, one of Europe’s most famous and most elaborate synagogues, its pulpit home to some of the greatest cantors of the century, was a symbol of Warsaw Jewry’s former prosperity and cultural sophistication. (After the war, an office building constructed on the site was plagued with insoluble structural and technical problems; a rumor persisted in Warsaw that the “ghosts” of the ghetto had indelibly sabotaged the new building.)

In the ensuing months, some Jewish units continued sporadically to fight, while the Germans attempted to pursue and kill any remaining Jews hiding among the ruins of the ghetto. By August 1943, however, the fight was over. In the last two weeks of the full-blown resistance (from April 29 until the date of the reported German victory), the Germans acknowledged their losses at 16 dead and 85 wounded, although historians have suspected that their casualties were significantly greater. The official German report also stated that they had killed and deported a combined total of 56,000 Jews in the final month of the uprising. Stroop was later sentenced to death by an American military court at Dachau. He was extradited instead to the new Polish People’s Republic, where he was also wanted as a war criminal. He was tried in 1951 in the Warsaw district court, and hanged on the site of the former ghetto that same year.

Itzik Fefer and the Soviet Regime

Soviet Yiddish poet Itzik Fefer (1900–1952) fashioned his homage to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and its victims in the form of an extended poetic work centered around the story of a lone boy who miraculously survived the battle. It was published in the United States by the left-leaning Yiddishist organization IKUF (Yidisher Kultur Farband—the Yiddish Cultural Organization) in 1945, and it came to Helfman’s attention shortly thereafter. It was not published in the Soviet Union until 1946.

Fefer was one of the most prominent poets of the Stalin era, and one of the group of Jewish poets—along with David Bergelson, David Hofshtein, Peretz Markish, and others—who were arrested, tortured, and murdered by the NKVD in Stalin’s anti-Jewish purges of the postwar terror. He was born in Shpola, in the Kiev district of the Ukraine, and he joined the Bund at the age of seventeen but left it two years later to join the Communist Party. That same year (1919) his writings began to appear in the Kiev Yidddish periodical Komunistishe fon (Communist Flag), and his first collection of poems, Shpener (Splinters), was published in Kiev in 1922 by Vidervuks (New Growth), an association especially geared to the young generation of Yiddish writers, which had its own publishing arm. Indeed, the Yiddish literary historian Zalman Rejzen [Reisen] assessed that first major effort of Fefer’s as “expressing the lyrical joy of the new generation,” and he compared him favorably with the proletarian Yiddish poet, Izi Kharik, together with whom, he felt, Fefer had "placed himself at the top of the group of Yiddish writers in the U.S.S.R., which has looked to the shtetl and introduced into Jewish literature sensibilities of the ordinary folk.”

In general, Fefer’s poetry has been characterized as “simple language” (proste), or “common speech”—literature that spoke to the masses of Yiddish readers in the years immediately following the Revolution who could not relate so easily to the more sophisticated and avant-garde writings of the much smaller Yiddish intelligentsia of that time. He spoke in proletarian-tinged terms about “organizing the blossoming worker writers” and of “the worker soldiers in the artists’ army.”

Fefer actively promoted the official party line and the proletarian cause in nearly all his writings, as well as in his extraliterary activities as an apparatchik involved with state-sponsored and state-sanctioned committees and organizations. Much of his poetry—its artistic merits aside—directly served the interest of Soviet communist ideology and of the Stalin regime and its cult of personality. Stalin, in which he glorified the de facto dictator (whose megalomania is now acknowledged) as a teacher and a visionary, became one of his best-known poems, though he was hardly alone among Soviet Yiddish poets in those sentiments. (“When I say Stalin—I mean beauty / I mean everlasting happiness....”)

As a Jew under a regime that we now know to have been violently anti-Semitic on various levels at various times, Fefer’s political and ideological alignment must be understood not simply as personal and professional survival, but in the context of the natural leanings and loyalties of much, if not most, of the mainstream of Soviet Jewry—especially in the years prior to the end of the Second World War. For a long time—despite the Great Terror of the 1930s and despite periods of restriction and forced abridgment even of secular Yiddish educational and cultural activity—much of that Jewish mainstream, which included the indoctrinated proletarian circles, remained committed to the professed ideals of the party, as well as to Stalin as their leader. For those Jews, Stalin and the party represented the bulwark against the Fascist threat; an assurance of continued advancement of the “new order”; an almost messianic antidote to the perceived ills, decadence, and built-in inequities of Western bourgeois societies; protection from so-called nationalist-imperialist and capitalist regression; and a defense against alleged plots to undermine Soviet security and the communist cause. Thus, for the proletarian Yiddish writers, the vitality and continuation of Yiddish literature itself was inextricable from communism. Fefer’s work is permeated typically with collective rather than personal concerns and with the prevailing principle and tone of continuous revolution. Serving the Revolution was inseparable from serving its authorities. For most of the world—including much of Soviet society—the undiluted truth about Stalin did not emerge until after his death, and then, publicly, only after Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s revelations in the 1950s of the grisly details, beginning with his famous “secret speech” to the 20th Party Congress in 1956.

Even earlier, however, when many party loyalists and even overtly pro-Stalinist sympathizers—including those in America—had begun to hear of the brutal purges and their accompanying murders, and even after word of the renewed post-1948 anti-Jewish campaign had started to spread, some people refused to reconsider their past assumptions. Often in the face of overwhelming evidence, some remained loath to condemn or even criticize the very regime they had championed for so long. When the tide turned ominously against leading Soviet Jewish cultural figures such as Fefer, little or no pressure from the outside was exerted on their behalf; and circulating reports of their impending doom were often dismissed by communist apologists as typical anti-Soviet rumormongering. Others excused the persecutions as “excesses” or aberrations, rather than considering them as inevitable by-products of Soviet totalitarianism.

During the early years of Stalin’s ascendancy, his policies appeared—for whatever self-serving reasons of Realpolitik in view of the significant numbers of Yiddish speakers and readers—to encourage secular Jewish (viz., Yiddish) cultural institutions, beginning with his commissariat during the first Soviet government. Only later were those policies reversed through a series of suppressions, purges, and liquidations of the bulk of those institutions, leaving only token remnants—such as a Yiddish art theater in Moscow or a few Yiddish periodicals that harnessed themselves to the party line—as “show” propaganda and public relations instruments.

In 1926 Fefer became an instructor in the Yiddish section of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. In 1927 he was one of the founders of the Ukrainian Association of Yiddish Revolutionary Writers (soon afterward the Yiddish Section of the All-Ukrainian Union of Proletarian Writers), whose journal, Prolit, he co-edited; and later he was an official spokesman for Yiddish literature on the boards of the unions of Soviet and Ukrainian writers. He also was a co-editor of Di royte velt (The Red World), and he edited the Almanac of Soviet Yiddish Writers in 1934. He survived the great purges and the terror of the 1930s, remaining in favor and receiving various Soviet medals.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, in June 1941, Fefer became the secretary of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (EAK) in Moscow—in addition to serving at the front with the Red Army, in which he attained the rank of lieutenant colonel. The Committee was established in order to promote the cause internationally of the Soviet Union’s life-and-death struggle in its “Great Patriotic War” against Germany, and to garner increased material as well as moral support for its military effort and for the Red Army. From its own communist perspectives, of course, the need for such intensified support went beyond the contemporaneous strategic planning of the Western Allies for victory against the Axis powers, which would be followed by rebuilding a defeated Germany not only as a postwar Western ally, but as a liberal democracy. One of the primary objectives of EAK and other similar Soviet anti-Fascist committees, therefore, was to lobby for the opening of a second front, which became the mantra of Soviet sympathizers in the West. Stalin saw EAK as a convenient vehicle for seeking Jewish support in the West—a tactic that he and the party viewed as distasteful but temporarily useful. They presumed that Jews, especially in America, had the collective financial means to lend significant material assistance and also that they possessed a potential influence over government and military policy that, of course, they never actually had. But the presumption was enough for Stalin to permit and even tentatively encourage theretofore forbidden contact with the West and with its Jewish leadership—contact that would later be used against EAK members and other Soviet Jewish emissaries after the war as evidence of anti-Soviet activity, nationalist sympathy, and even espionage. Also, Stalin presumed that knowledge of Germany’s war against the Jews would contribute to Western Jewry’s desire to aid the U.S.S.R.

In 1943, together with the famous Soviet Yiddish actor and de facto spokesman for Soviet Jewry, Solomon Mikhoels, Fefer made an official visit to England, Canada, Mexico, and the United States on behalf of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. Gatherings such as the mass “peace rally” at the Polo Grounds in New York were attended by enthusiastic Jewish as well as general procommunist crowds and workers’ groups. Fefer also spoke out publicly in New York about German atrocities against European Jewry—something that was not much mentioned openly then in America by the mainstream Jewish leadership, partly so as not to provide ammunition to those American anti-Semites, pro-Fascists, and isolationist antiwar factions who might welcome “proof” that the American war effort in the European theater was indeed the result of Jewish and “international Zionist” instigation on behalf of European Jewry.

During the war, when some of the Soviet restrictions against patently Jewish literary expressions were relaxed, at least in part to facilitate Jewish cooperation and support, Fefer wrote his poem “Ikh bin a yid” (I Am a Jew), which has been described not only in terms of expressing Jewish pride, but as a “sample of Soviet Jewish patriotism.” In his 1946 poem “Epitaph” he spoke of being buried in a Jewish cemetery, and he articulated the hope that he would be remembered as one who had “served his people.” These works, together with Di shotns fun varshever geto, appear to represent an awakening and intensification of Fefer’s Jewish consciousness. The extent to which they contributed directly to his persecution and eventual execution is not entirely clear. It is known, however, that “Ikh bin a yid” was quoted in 1952, in connection with the prosecutorial proceedings against the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, as evidence of his “nationalist deviation.” In any case, by 1948, despite official party line denials of anti-Semitism (and its technical constitutional illegality in the U.S.S.R.), Stalin had come to fear any thriving Soviet Jewish culture as a serious threat—ranging from mere furtherance or fertilization of the Yiddish language (now deemed far less necessary to the party in view of the vastly reduced Yiddish readership) to Jewish cultural preservation or solidarity. And those who, like Fefer, had contact with the West during the war were now suspected of being irrevocably tainted potential recruits as enemies of the state. Once the Soviet Union had prevailed in the war, EAK, now no longer useful to the regime, was considered a liability as a perceived representative of Soviet Jewry. It was disbanded in 1948, and many of its leaders were executed. Apart from concealed or “mysterious” deaths, subsequent kangaroo trials of fifteen people linked to EAK resulted in thirteen of them being executed by firing squad in 1952.

By the time the State of Israel was established in 1948 and recognized by the Soviet Union, Fefer had embraced the Zionist cause as an appropriate concern of world Jewry; and he even credited Soviet heroism during the war with contributing to the ultimate realization of Zionist political aspirations. This could only have magnified the precariousness of his situation. As a foreign policy strategy, the U.S.S.R. supported Israel’s founding as a reduction of British imperial influence and as a potential ally. But within the U.S.S.R., Zionist sympathy and enthusiasm for the new state were read more clearly than ever as dangerous Jewish nationalism and potential disloyalty. Having already lost his benefit to the regime, Fefer’s combination of Yiddishist cultural nationalism and Zionist sympathy had to have signaled a sense of Jewish particularity that might only impede the mandated progress of accelerated assimilation.

Fefer was arrested in December 1948 and held at the infamous Lubyanka Prison. When Paul Robeson, the famous American black singer, actor, and social activist, as well as avowed communist and Stalin admirer, visited the Soviet Union in 1949 on one of his periodic concert tours, he insisted on seeing Fefer, whom he had befriended on earlier visits as well as during the 1943 EAK mission to the United States (Robeson had also appeared at the Polo Grounds “peace rally”). Although it is assumed that he did not know for certain of Fefer’s arrest, he had begun to suspect that Fefer might be in danger. According to his son’s account, Robeson later admitted that he sensed anti-Semitic vibrations and that these were becoming transparent locally in the press, and he became concerned about the fate of his friends among the Jewish literary and artistic circles. Mikhoels had been murdered the previous year, on Stalin’s orders (although Stalin’s role was only suspected then). Fefer was taken out of prison for a day and brought to Robeson’s hotel room for an unguarded visit. Knowing that the room was bugged, the two spoke neutrally, but Fefer made it clear to Robeson—through handwritten notes (which Robeson later destroyed), coded gestures, and other unmistakable body language—that reports of the new terror were true, that many other Jewish cultural figures had been arrested, and that he himself was doomed to eventual execution. When Robeson returned to the United States, however, he refused to acknowledge that there might be any anti-Semitic campaign in the Soviet Union, much less that Fefer was in trouble: “I met Jewish people all over the place,” he told the press, “[and] I heard no word about it [anti-Semitism or danger for Jews].” Fefer was in fact returned to Lubyanka Prison. He was shot, probably on August 12, 1952, after being accused of Jewish nationalism and of spying for America.

Even after Khrushchev’s secret speech in 1956, Robeson refused to sign any statement concerning Fefer’s fate or their visit. (He did, however, tell his son what had actually happened, on condition that it be kept secret until well after his death.) Despite his genuine feelings of friendship for Fefer, Robeson was one of those who could not bring themselves to criticize the Soviet Union, or even Stalin, regardless of the undeniable revelations—clinging to the dogma that, on balance, both still represented a force for universal peace and justice. (Moreover, Robeson held the unsupportable conviction that the Soviet Union somehow represented the hope of the future for American blacks and the key to reversing their subjugation, predicting in the midst of the cold war, in a tone almost calmly suggestive of incitement, that American blacks would therefore refuse to fight in any war with the Soviet Union.) “He believed passionately that U.S. imperialism was the greatest enemy of progressive mankind,” wrote Paul Robeson Jr. “In such a context Paul [Sr.] would not consider making a public criticism of anti-Semitism in the U.S.S.R.” Thus there was no lobbying in America to save Fefer, and his murder, which was not even substantiated until later, went relatively unnoticed there outside Yiddishist circles. By the time of Khrushchev’s revelations, Fefer could still be viewed, by those who wanted to do so, as just one of the many victims of Stalin’s personal paranoia rather than as an indication of any inherent fault in the Soviet system. Following the rejection of Stalinism in the U.S.S.R., Fefer was “rehabilitated,” and parts of his works were published there in Russian translation.

It is now widely accepted that Fefer was an informer for the NKVD for a number of years and that, as a defendant himself, he cooperated with the state in implicating fellow EAK members at their trials. Thus, some post–Soviet era revisionist considerations tend to compromise his reputation; but the entire issue is intertwined both with the paranoia of the times and with what we know to have been state and secret police duplicity and fabrication. For one thing, Fefer, like the other defendants—who confessed and then retracted—was subjected to torture. For another, although archives have been unsealed since the collapse of the Soviet Union, documents such as those that purport to describe Fefer’s role with the police and in the trials are highly questionable, as they were created by the secret police. In any event, it is also now generally believed that Fefer’s death sentence had already been determined before those trials began.

Di Naye Hagode: Helfman's Magnum Opus

Di naye hagode does not, as the title otherwise infers, take the form of a refashioned or alternative Passover Haggada or seder per se, along lines parallel to alternative formats created in America by such secular Jewish groups as the Arbeter Ring (Workmen’s Circle) or the Labor Zionist Farband (see the Third Seder of the Arbeter Ring in Volume 12), or by kibbutzim in Israel—who reinterpreted and reimagined the Passover narrative and the entire seder ritual in nonreligious terms according to their own particular national, social, cultural, or historical ideologies. It does, however, seize upon and develop—musically and dramatically—the poet’s suggestion that the German war of annihilation against the Jews and the heroic Jewish resistance constitute a seminal turning point in the history of the Jewish people, in which that history has become forever altered to address new heroes and to include a new focus. In that sense, the piece might be viewed as a poetic reconsideration and reinterpretation of the conventional Passover narrative, as well as of the role of collective memory in it.

Like the original poem, Helfman’s work emphasizes solemn celebration of Jewish heroism over the centuries-old perception of Jews as helpless, submissive victims—over whose fate future generations agonize. And it proposes that a fitting memorial is perpetual outrage at the perpetrators rather than mourning for the murdered resisters. Unlike reliance on Divine miracles in the biblical account, this work extols human courage and resoluteness as the path to liberation and as a worthy memorial. For Fefer and Helfman, as for many nonreligious or religiously disaffected but culturally identified Jews, this type of narrative seemed more relevant, more real, more galvanizing, and even more worthy of remembrance than the events of the Bible. It might be assumed from a theoretical-historical perspective that in ancient Egypt, the Israelites could have chosen to remain slaves while still surviving physically. In the Holocaust, however, the Jews’ doom was sealed not by what they agreed or refused to do, and not by their beliefs or actions, but simply by virtue of the fact that they were Jews. In that context, upon which Di naye hagode focuses, only heroic armed resistance—despite the obviousness of its certain eventual failure—could have even the chance of modifying that doom and paving the way for some form of ultimate Jewish survival. “Death will overtake us in any event,” rang the call to arms of the United Partisans Organization, “but this is a moral defense; better to fall in the fight for human dignity—to die as free fighters—than to live for a little while by the grace of the murderer.” Many if not most in the Resistance knew they could not prevail, but as one survivor recalled, “there is great honor to be celebrated in this resistance without victory—in the decision that requires the strongest moral convictions.”

Di naye hagode reflects some of the formal structure of a standard Passover Haggada—most overtly in the first musical number, Ma nishtana. The seder ritual, which was based originally on the Greek symposium format, is infused with a quasi-Socratic question-and-answer approach, whereby the story of the exodus from Egypt is related, discussed, and amplified in response to questions posed by the participants—especially the children. By tradition, the youngest person at the seder, representing the youth of each generation, commences the process by asking the “Four Questions”—a formula that refers to four of the basic features of the seder and opens with the words, ma nishtana halayla haze mikol haleylot? (Why and how is this night different from all other nights?) Fefer transformed that part of the Haggada into a central question to be asked on each anniversary of the Uprising, prompting the recollection of the events. Here, Helfman employs the most widely known chant pattern in Ashkenazi tradition for this text—the chant formula known as lern-shtayger (study mode), which is used in Talmudic study and recitation to facilitate the memory of text passages. He even sets up the question-answer element with the response of the women’s voices at a different pitch level. The words at the end of the sixth number, A linder april (A Mild April), refer to the beginning of the established narrative in answer to those Four Questions: Avadim hayinu l’faro b’mitzrayim (We were slaves of the Pharaoh in Egypt...). Here, of course, they apply to the contemporary incarnation.

The prophet Elijah, who will arrive to herald the coming of the Messiah, is an important element of the traditional seder ritual. He is said to visit every seder and to take a sip of the special goblet of wine reserved for him at each table, and the participants open the door for him and express their hope that he will arrive soon. Thus in the seventh number, Vet kumen? (Will He Come?), the chorus asks whether a savior (“the prophet”) will come to the ghetto. “The white-robed fathers” in an ensuing passage of the narration refers to the kitl—a white garment, representing holiness, which is worn in many customs by the “head of the household” who presides over the seder. And the reference to “the queens of each house” refers to their wives, traditionally perceived as the “Passover queens.”

After opening the door for Elijah at the beginning of the second half of the seder, those gathered around the table pronounce the words shfokh ḥamat’kha al hagoyim asher lo y’da’ukha...ki akhal et ya’akov (Pour out Your wrath on the nations who have rejected You...for they have sought to destroy the people Israel). This is a natural expression in the context of this work, and reference to it recurs a few times.

Di naye hagode received its world premiere in 1948 (in its unorchestrated version) at New York’s Carnegie Hall. The occasion was the twenty-fifth anniversary concert of the Jewish Peoples Philharmonic Chorus, conducted by the composer. (Inexplicably, the chorus—essentially the same one Helfman had begun directing in 1937—billed itself then as the People’s Philharmonic Choral Society, although it subsequently returned to its earlier name.) That performance also included an important dance component and staging by Benjamin Zemach, the eminent choreographer and creator of modern Jewish dance forms. Dance was also part of subsequent performances in Montreal (1949), in Los Angeles at the Wilshire-Ebell Theater (1950) where it was sung by the Jewish People’s Chorus, and in Santa Monica, California (with full orchestra), among other venues. The work was featured by the Jewish Peoples Philharmonic Chorus in its 1964 memorial tribute to Helfman, performed at New York’s Town Hall.

As a composer, Helfman was essentially a miniaturist who excelled in the smaller forms. More than once he expressed to close associates and friends his regret that he had never written, or had the patience to complete, a magnum opus. Of all his works, however, Di naye hagode, with its overall musical-structural arch, its sense of inspired artistic unity, and its judicious balance, probably comes closest to that wish. Indeed, the consensus among those familiar with his music has long been that this was Helfman’s most ambitious and most powerful work.

Lyrics

Sung in Yiddish

Text: Itzik Fefer

NARRATOR:

This is the story of a city in desolation. A city of ghostly shadows, where once Jews lived and prayed and worked. This is the story of a fateful evening, of unspeakable days when Jews were huddled in the frightful subcellars of the ghetto to read again the Haggada, the ancient recital of the struggle for freedom. And when the brutal hordes of the enemy came into the ghetto with their tanks and their poison gases to exterminate them, the Jews left off reading the Haggada and rose and met the enemy empty-handed but head-on, writing a new Haggada in their blood. This is the story of a city. This is the story of a fateful night. This is the story of the New Haggada.

Ma nishtano halaylo haze mikol haleyloys? How does this night differ from all other nights in the year? Why? Why? Those ghostly columns of marching shadows—these are the shadows of those who have perished. Aimlessly they wander through the desolate streets, groping in the darkness of burned-out ruins, wailing over the fate of mothers and children. They cannot find their last resting place. They have not even spoken their last prayers yet. Thus begins the New Haggada, the New Exodus. Ma nishtano halaylo haze mikol haleyloys? How is this night different from all other nights in our lives?

MA NISHTANO

CHORUS:

How is this night different from all other nights?

Why? Why is this night different from all other nights...of our lives? Why?

They roam through streets and alleys,

They knock in darkness on wide-open doors,

They mourn near ruins, they sleep on hard floors,

They fall upon dark, cold dirt roads.

They rise once again and wander exhausted

Through gray abysses, over verdant peaks.

They have not yet recited their confession;

They cannot yet find their rest.

Early in the morning, late at night,

They roam, the shadows of the Warsaw Ghetto.

GEBENTSHT (BLESSED)

NARRATOR:

Forever blessed are they who remember the graves, the graves wherein lie our people so great and so tormented.

Blessed are they.

CHORUS

Blessed are they who remember the graves

Where our people lie, our great, our poor.

RIBOYNE-SHELOYLEM (MASTER OF THE UNIVERSE)

NARRATOR:

O Father in Heaven, can it really be that in this city of desolation

our people once lived and worked and bargained and played with their children?

CHORUS:

Master of the Universe!

Here men lived and worked, wept and sang.

Here they would curse, here they would bless;

Here merchants haggled with customers.

NARRATOR:

O Father in Heaven, can it really be that here children were lovingly rocked in their cradles, and joyful sounds of merrymaking were heard at splendid weddings?

CHORUS:

Here they knitted and danced and shouted,

Here they rocked the babies in their cradles,

Here children clung to their mothers,

Here they reveled at large weddings.

INTERLUDE–WEDDING SCENE

NARRATOR:

And so begins the New Haggada. It was spring. Again it was Passover, and joyous songs were heard blended with the strains of the sad avodim hayinu: slaves we were in the land of Egypt. Passover had come again and the mild April winds touched the young leaves.

A LINDER APRIL (A MILD APRIL)

CHORUS:

A mild April spread over the orchards,

And the birds and grass rejoiced,

That, just as always, the lovely spring arrives.

“We were slaves [of Pharaoh in Egypt].... ”

VET KUMEN? (WILL HE COME?)

NARRATOR:

What tragic messenger flies through the ghetto?

CHORUS:

Will the prophet [Elijah] come? Will the savior come?

Whence will help come to the Ghetto?

From East? From West? From South? From North?

VET KUMEN? (CONTINUED)

NARRATOR:

The terrible news has routed the seder. All eyes are aflame, all hearts filled with courage. They come, they come, the poison-filled hordes. Slayers, they come.

CHORUS:

[Even if just one hundred remain]

May the wrath burn for hundreds of generations,

And whoever distances themselves from maintaining the wrath

Shall be forever cursed.

NARRATOR:

But they were met. They were met with lightning and thunder by the white-robed fathers, by the queens of each house. Each room is a bastion. Each home a fortress. They shoot. They shoot in the ghetto.

UN OYN S'VET NOR A MINYEN FARBLAYBN (AND IF TEN SURVIVE)

CHORUS:

Then this minyen [quorum of ten] with strength in its arms

Shall not come to our graves bedecked in sighs.

Let the minyen not visit our graves gushing hot tears.

Even if only ten in all remain,

Let this conscience be ablaze in them for generations;

And the conscience of ages should spur them on

In the vicious final struggle!

And if into these Jewish fingernails shall fall

Even just one butcher to be strangled and choked,

One who will not live to see the crack of dawn,

I will, from the grave, bless these sons of mine.

DI SHLAKHT (THE BATTLE)

CHORUS:

There’s shooting in the Ghetto, and the Ghetto replies,

Hate with hate, fire with fire.

Guns converse here.

The Ghetto seethes with new infernos.

ZEY ZAYNEN GEKUMEN (THEY CAME)

CHORUS:

They descended like hordes from the steppe

With venom in their eyes, with satanic faces,

Like robbers who come stealing others’ possessions.

They were met with thunder and lightning;

It rained lead in the Warsaw Ghetto.

The pale Jewish men, kings in white kitls,

The slender women, the queens, rich and poor alike

Boldly threw themselves on tanks

Unarmed, but with an iron wrath.

Every house turned into a fortress.

Every window sputtered forth wrath.

Now the wind is saying, “Pour out Your wrath.”

Bloody rivers streamed on;

And the stars were like weeping eyes,

And the Passover Haggadas were left reading themselves....

NARRATOR:

The seder is deserted. The wind now alone chants the prayers.

The sobbing stars behold the orphaned Haggada.

Out of all this unspeakable destruction only the young boy is left. Tempered in fire and bursting shells, he stands on the last remaining tower. He, the symbol of the last youth of the Ghetto. Was it only yesterday when, as a child, he played in the streets?

DOS YINGL (THE BOY)

CHORUS:

Right here, not too long ago, when evening would fall,

He used to ride on brooms with the other boys.

They used to ride wooden horses;

They used to fight with wooden swords.

They dreamed about great battles

With real guns and real spears,

With real soldiers, towering like giants...

NARRATOR:

How quickly has his childhood ended! And what are the worldly possessions now left to him? Only two hand grenades, a gun, the torn flag of his people. He climbs up the broken wall of the tower. He wraps his body like a high priest in his prayer shawl, and clinging to its folds in everlasting embers, he fires two bullets and leaps into space.

DI FON (THE BANNER)

CHORUS:

The boy takes the fluttering banner

And wraps together its broad folds

And throws it, like a light shawl,

Over his shoulders—the shoulders of the Warsaw boy;

And tosses himself from high atop the flaming building.

DER TOYT (THE DEATH)

CHORUS:

Death is his life. The banner—his will and testament.

It is his heritage, his faith, his hope,

With it his way to eternity is open!

NARRATOR:

Who will now come to console us? Will a prophet appear to deliver us? When will he come? What is his name? Still the Ghetto’s shadows suffer and wonder. “If out of all our people only one hundred should remain, then let, in these hundred, the flame of generations thunder and burn.”

SHFOYKH KHAMOSKHO (POUR OUT YOUR WRATH)

CHORUS:

Pour out Your wrath upon the enemies....

Pour out Your wrath upon all the enemies..

NARRATOR:

If not one hundred, or even fifty, but only ten shall survive, then let power strengthen the arm of this minyen, this quorum, not to shed bitter tears on our graves, not to weep on our tombs, but to let the conscience of ages burn in the hearts of men for now and forever. Then, only then, from our grave we shall give them our eternal blessings.

RUM UN GEVURE (GLORY AND HEROISM)

CHORUS:

And above all shines the glory and heroism,

From the battle on the Volga, from Russia’s bayonets,

From that blessed and precipitous storm,

Which comes in late summer after the harvest.

NARRATOR:

And so begins the New Haggada. Ma nishtano halaylo haze mikol haleyloys? Why is this night different from all other nights? Because on this seder night we remember them all, those nameless shadows who have died so that we may live; who have borne their suffering so that we may live in freedom. In us and our children, their blessed memories shall live on and on.

AZA DER GEBOT IZ (SUCH IS THE COMMAND)

CHORUS:

How is this night different from all other nights?

Why is this night different from all other nights...of our lives?

They roam, the shadows of the Warsaw Ghetto.

They roam like prophets beheaded,

They bear their cruel fate with pride

And their secret dream is danger.

They wander the world like rebels,

Who haven’t surrendered their ammunition on the battlefield.

The Vistula knows them and so too the Nieman [River]

And their names are exalted along the Jordan;

And the Volga spies them through the smoke of the North,

And the mountains have not impeded their way.

Such is the command,

Such is fate:

To die in order to be reborn.

So begins the New Haggada....

Credits

Composer: Max HelfmanPerformers: Theodore Bikel, Narrator; Choral Society of Southern California; Los Angeles Zimriyah Chorale; Nick Strimple, Conductor; Young Musicians Foundation Debut Orchestra

Publisher: MS