Tracks

Liner Notes

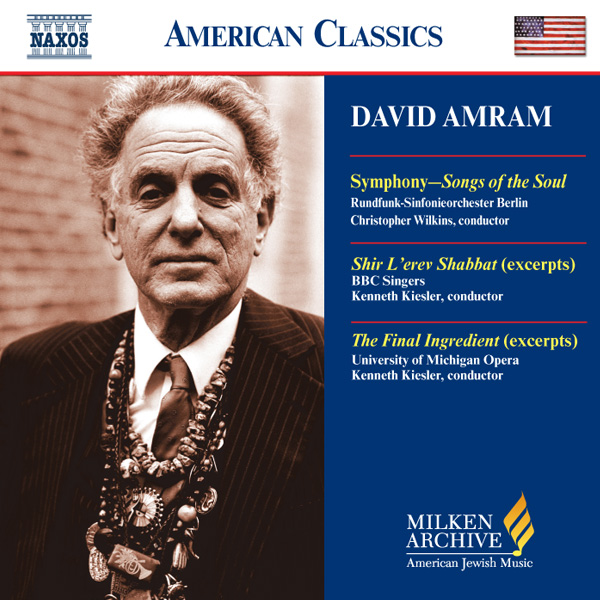

Although he uses liturgical melodies and references in many of his works and has also composed some individual liturgical settings, Shir L’erev Shabbat, a unified Sabbath eve service, represents David Amram’s major foray into sacred music. Like so many Sabbath services by 20th-century American composers, this was commissioned by Cantor David J. Putterman and the Park Avenue Synagogue in New York.

In the spring of 1943, Cantor Putterman, who served the pulpit of the Park Avenue Synagogue—a nationally prominent and religiously centrist congregation affiliated with the Conservative movement—presented his first “Sabbath Eve Service of Liturgical Music by Contemporary Composers.” That service offered, as world premieres, the first fruits of his ambitious experiment: the commissioning of well-established as well as promising younger American composers, non-Jews as well as Jews, to write for the American Synagogue and its liturgy. There were some precedents in Europe during the 19th century, notably in Vienna and Paris, for invitations to local Jewish and Christian composers for synagogue settings. Some American synagogues also preceded Putterman in commissioning new music for Jewish worship—in some cases by highly important composers. But Putterman’s project, unlike those occasional or one-time occurrences, was soon designed to function in perpetuity on an annual basis.

Over its decades-long span, Putterman’s Park Avenue Synagogue program sought to encourage serious artists—who were often outside the specifically Jewish liturgical music world—to contribute to Jewish worship, each according to his own stylistic language without imposed conditions. In addition, Putterman’s practical aim was to accumulate an expanding repertoire of sophisticated music suitable for American synagogues, many of whose worshipers were no strangers to contemporary developments in the world of serious cultivated music.

The very first new music service that spring included world premieres of settings by Alexandre Gretchaninoff, Paul Dessau, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Hugo Chaim Adler, and Max Helfman—all commissioned expressly for the occasion—along with other contemporary but preexisting works by accomplished synagogue composers. The experiment proved immediately successful, and Putterman soon organized permanent funding for the annual commissions and premiere performances. The underlying mission was stated in the printed programs furnished for the congregation: “The program is dedicated to the enhancement of Jewish worship; to a wider diffusion and utilization of the resources of Jewish music; and to the encouragement of those who give of their lives and genius to its enrichment.”

Those special Friday evening services of new music soon became not only important occasions for the wider Jewish community, but also eagerly anticipated annual events on New York’s general cultural calendar; and they attracted considerable national attention as well. For the composers mostly associated with the general music arena, the commissions often constituted unique artistic challenges. For those already devoted in some measure to Jewish liturgical expression, the annual commission award became a much coveted honor as well as a prestigious opportunity—almost a “right of passage” in some perceptions. Indeed, by the end of the 20th century, many of the most significant works in the aggregate literature of American synagogue music had been born as Putterman commissions.

Over the years, dozens of successful composers received Putterman commissions and had their music presented at those annual services. The roster includes, among many others, such names as Leonard Bernstein, Kurt Weill, Darius Milhaud, Herman Berlinski, Stefan Wolpe, Alexandre Tansman, Robert Starer, Jack Gottlieb, Lazar Weiner, Yehudi Wyner, Miriam Gideon, Marvin David Levy, Leo Smit, Lukas Foss, Jacob Druckman, Leo Sowerby, and David Diamond. Of equal interest from a historical perspective is the list of many of America’s most prized composers who were invited by Putterman but who, for one reason or another, declined: Arnold Schoenberg (who did seriously contemplate the proposition), Samuel Barber, Ernest Bloch, Paul Hindemith, Paul Creston, Walter Piston, Norman Dello Joio, Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, Bernard Hermann, William Schuman, and Igor Stravinsky—to cite only some.

The first seven annual contemporary music services comprised individual settings of specific prayer texts by a variety of composers. Beginning with the 1950 service—and for more than a quarter century afterward, with the exception of special anniversaries or retrospectives—entire musical services as artistically unified works by single composers were commissioned and presented each year.

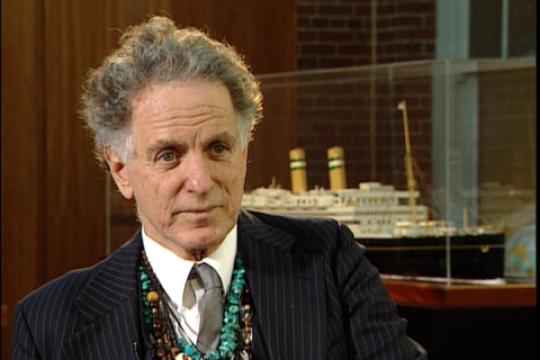

Cantor Putterman first met Amram in the summer of 1957 at a “Shakespeare in the Park” production in Central Park, for which Amram had written the incidental music. That production was his first collaboration with Joseph Papp. Impressed with Amram’s gifts and promise, Putterman told him after the performance that he would want him “someday” to write a work for the synagogue. That noncommittal invitation became Putterman’s official commission only three years later, and the result—Shir L’erev Shabbat—was premiered in 1961. It was performed subsequently at the Washington (D.C.) Hebrew Congregation in 1965, and in New York at Carnegie Hall in 1967, with tenor Seth McCoy singing the cantorial solo parts.

The work encompasses both the preliminary kabbalat shabbat (welcoming the Sabbath) and Sabbath eve services (arvit), but—with the exception of the opening ma tovu, a nonobligatory text from Psalms that is used for many liturgical occasions as a prelude but is not specifically part of either the kabbalat shabbat or arvit liturgies—the excerpts here are from the Sabbath eve service proper. In composing the service, Amram did not consciously incorporate preexisting traditional material, nor did he base his settings on traditional Ashkenazi prayer modes or motifs. He relied rather on internal and implied musical ideas suggested to him by the texts themselves—the rhythms and cadences of the words and phrases, and their emotional parameters as he perceived them. “I just tried to let the music of the prayers, the music of the words, and the spirit dictate what to write,” he later recalled.

The opening three-note motif in the organ introduction to ma tovu, which imaginatively spans a major ninth, serves as a unifying device for the entire service, and it reappears throughout. Amram thought of this motif, which he recalled having heard sung by a lay cantor in a Frankfurt synagogue, as somehow reminiscent or “symbolic of a giant shofar”—a highly personal interpretation unrelated to the Sabbath service. Throughout the work, the solo vocal lines are spacious and expansive, creating an aura of openness and breadth. That feeling is reinforced by the harmonic structure, which is framed by open chords and especially open fifths, with effective superimpositions of independent fifths on one another. This technique creates a sonorous quality that is particularly well suited to the combination of mixed chorus and organ, lifting the organ out of a purely accompanimental role. The style and harmonic language falls somewhere between free and extended tonality, with faint hints of polytonal and even nontonal flavors. Part of the artistic freedom here lies in that very juxtaposition of tonal and nontonal elements, which can sound at once refreshingly arbitrary and musically logical. The formal structure follows no preordained design, but is generated by the composer’s innate sense of expressive impulse: his sense of feeling and emotion underlying the texts, and his interpretation of those emotional dimensions.

“The experience of writing this service was like a delayed bar mitzva for me,” said Amram, who did not have a formal bar mitzva at age thirteen, because his father was in the service during the war. “I gained a new part of my Jewish manhood—at thirty rather than thirteen. By acknowledging my own ancestral vibrations, I could enjoy life every second more, just by knowing more who I was and am.”

Predictably, the premiere brought out an unconventional crowd for a Sabbath worship service, including many of Amram’s Greenwich Village jazz club comrades—Jews and non-Jews—who had never been to a synagogue, and, as he characterized them, many “Jewish hipsters who hadn’t been to a synagogue since they were children.”

Amram later orchestrated two of the settings, Sh’ma yisra’el and Yigdal, and used them in his opera The Final Ingredient.

Lyrics

(Excerpts)

MA TOVU

How lovely are your dwellings, O House of Israel. O Lord, through Your abundant kindness I enter Your house and worship You with reverence in Your holy sanctuary. I love Your presence in this place where Your glory resides. Here, I bow and worship before the Lord, my maker. And I pray to You, O Lord, that it shall be Your will to answer me with Your kindness and grace, and with the essence of Your truth that preserves us.

BAR'KHU

Worship the Lord, to whom all worship is due.

Worshiped is the Lord, who is to be worshiped for all eternity. Amen.

SH'MA YISRA'EL

Listen, Israel! The Lord is our God.

The Lord is the only God—His unity is His essence.

MI KHAMOKHA

Who among all the mighty, can be compared with You, O Lord? Who is like You, glorious in Your holiness, awesome beyond praise, performing wonders? When You rescued the Israelites at the Sea of Reeds, splitting the sea in front of Moses, Your children beheld Your majestic supreme powerand exclaimed: “This is our God: The Lord will reign for all time.” And it is further said: “Just as You delivered the people Israel from a superior earthly military power, so may You redeem all from oppression.” You are worshiped (He is worshiped, and His name is worshiped), who thus redeemed Israel. Amen.

KIDDUSH

You are worshiped (He is worshiped, and His name is worshiped), our God, King of the universe, who creates the fruit of the vine. Amen. You are worshiped (He is worshiped, and His name is worshiped), our God, King of the universe, who has sanctified us through His commandments and has taken delight in us. Out of love and with favor You have given us the Holy Sabbath as a heritage, in remembrance of Your creation. For that first of our sacred days recalls our exodus and liberation from Egypt. You chose us from among all Your peoples, and in Your love and favor made us holy by giving us the Holy Sabbath as a joyous heritage. You are worshiped (He is worshiped, and His name is worshiped), our God, who hallows the Sabbath. Amen.

Credits

Composer: David AmramPerformers: BBC Singers; Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, Organ; Kenneth Kiesler, Conductor; Richard Troxell, Tenor

Publisher: C. F. Peters Corp

Coproduction with the BBC