Tracks

Liner Notes

Toch’s last years were filled with creative resurgence and renewed artistic energy, and during that brief time frame he wrote three symphonies. Only a few years before his death, in the course of searching for an opera subject, he became engrossed in the 1957 novel Jefta und seine Tochter (Jephta and his Daughter) by his fellow German émigré Lion Feuchtwanger. The novel is based on an incident in the biblical Book of Judges (11:30–40), and Toch settled on that story for his opera. But as his grandson later related, he became so driven by the project that his enthusiasm turned to impatience, and he was ultimately unable or unwilling to wait for his librettist to make a workable translation and text. He proceeded instead to create a purely symphonic programmatic work inspired by and based on the Jephta story—a “rhapsodic” tone poem. This became his one-movement fifth symphony, describing in abstract instrumental terms the unfolding of the biblical story of Jephta, its tragic conflicts, and the emotional impact of its dilemma.

The Book of Judges (shoftim) is so titled in reference to its accounts of a series of leaders of Israelite tribes, or groups of tribes, during the period after Joshua’s death, during the military consolidation and completion of the conquests of the land of Canaan, but prior to the solidification of the institution of monarchy in ancient Israel. These men were not necessarily or exclusively “judges” in the modern judicial sense of arbiters, but rather military leaders and rulers in the defensive campaigns against foreign encroachment and attack.

The prevailing view among modern biblical scholars holds that Joshua 1–11 and Judges 1 provide two alternative accounts of the Israelite conquest of the land, and that the conquest probably occurred in a serial, tribe-by-tribe assault on different portions of the land, as suggested by the Book of Judges, rather than as a unified and mostly successful campaign under Joshua. The eminent scholar Yehezkel Kaufman placed the period of the Jephta story in a second wave of “freedom wars” during which the Israelites were engaged in defensive battles against periodic enemy resurgence and aggression following the initial conquest period. In the biblical account, Jephta was a ”judge” for six years, during which time he was victorious over the Ammonites.

The Jephta story is introduced against a backdrop of the people having reverted to idolatry and then having removed the idols after Divine rebuke. The “illegitimate” son of Gilead and an unnamed harlot, Jephta was driven away by his father’s other sons, and he became a warrior and a leader of unsavory elements in the land of Tob. Later, when a territorial dispute with the Ammonites arose out of the earlier Israelite conquest of Canaan and escalated into an invasion, the elders of Gilead, knowing of Jephta’s warrior reputation, recalled him and asked him to become their chief (katzin) in repelling the Ammonites. Jephta agreed only on condition that after he had prevailed in the war against the Ammonites, he would remain their leader in peacetime as well.

Before engaging the Ammonites in battle, Jephta attempted to negotiate a diplomatic settlement, but he was rebuffed. He then made a vow to God that if He would deliver the Ammonites into his hands, he would demonstrate his gratitude by sacrificing as a burnt offering to God whatever was the first to emerge from his house upon his return. In a horribly ironic moment worthy of Greek tragedy and vaguely suggestive of Iphigenia, it was his own daughter—his only child—who was the first to come out of the house to greet him, and he felt nonetheless obliged to fulfill his sacred vow. The Bible relates that “he did as he had vowed”; that she was (or remained?) a virgin—i.e., that she never had a fulfilled life; and that she accepted her fate, asking only for two months to “mourn” the situation. It subsequently became a custom for Israelite women to commemorate the incident with a four-day mourning period during which they would chant dirges in memory of Jephta’s daughter. Some modern scholars translate the applicable passage as reading “she became an example in Israel” rather than “it became a custom in Israel,” and some scholars interpret the annual gathering as one of celebration rather than mourning.

Apart from any possible historical bases, at least three principal issues or types of questions are generated by the story: 1) whether or not, according to the narrative and its author’s intent, Jephta actually did kill his daughter in fulfillment of the vow; 2) if that is accepted as the intent of the story, what if anything is the significance of the outcome or the purpose of relating it; and 3) on an underlying level, apart from the daughter’s life or death, what is the story about: Jephta’s daughter or Jephta’s vow? Human sacrifice or the matter of vows to God in general? And is the nature of either the daughter’s death or the balance of her life ultimately relevant to the central point of the story?

Consideration of the first issue can itself pose a more basic problem on the surface: How could any interpretation allow for even the possibility of the daughter’s physical sacrifice, regardless of a vow, inasmuch as human sacrifice under any conditions had been condemned and categorically forbidden in the Torah (the Law or Teaching), which was purportedly received by the Israelites in the biblical chronology well before their initial entrance into Canaan under Joshua? From either a historical or a literary-biblical perspective, is it at all possible that there could have been child sacrifice among Israelites at that stage without the perpetrator being judicially condemned and punished as a murderer? The answer may not be simple or automatic. True, the incident in Genesis concerning the binding of Isaac for sacrifice, known as the akedat yitzḥak, where God ultimately stays Abraham’s hand, is traditionally cited as having firmly established the blanket prohibition of child sacrifice and as illustrating its unacceptability in a Mosaic departure from pagan practice. But modern biblical scholarship has utilized linguistic studies to determine that sections of the Book of Judges may actually predate the writing of the akedat yitzḥak story—that such parts of Judges (the “later” book) may therefore be older in their written form than the ḥumash (the Five Books of Moses, which form the written Torah), and that there were in fact incidents of child sacrifice among ancient Israelites prior to the dissemination of the akedat yitzḥak story. Thus at least the possibility of physical sacrifice in the Jephta account does remain for literary consideration.

As one would expect, postbiblical explicatory, exegetical, and higher critical literature from the Talmud to 20th-century scholarship has encompassed numerous and varied positions and interpretations of the Jephta story—ranging from literary-critical to historical, from theological to moralistic approaches and methods, and resulting in positions spanning a spectrum from literal to purely allegorical or metaphorical readings. But even among those camps, past and present, that have espoused an actual physical sacrificial conclusion to the story (i.e., the daughter’s immolation), that outcome generally has been treated as historically exceptional rather than as any indication of an acceptable norm, even at that early stage of ancient Israel.

The Aggadic literature (the Midrash and the parts of the Talmud concerned with legend and myth as explanatory devices, as opposed to legal issues) views Jephta in general as one of Israel’s least worthy, least knowledgeable, and least astute judges of the period. Both the Talmud and the Midrash condemn him for making such an imprudent vow in the first place, as well as for carrying it out—in whatever form. The very form of that condemnation, of course, can be (and has been) interpreted as implying acceptance of physical sacrifice as the story’s conclusion. Yet, how and in what form the vow was implemented—whether by actual death or as a nonlethal “sacrifice” of sorts—is not explicitly stated in those sources. But even if the physical sacrifice is assumed therein, two further significant points are stressed: 1) the illegitimacy and inapplicability of the vow itself, and therefore its nonbinding nature, since any vow of sacrifice by burnt offering even then could have had legal force only with reference to kosher animals (those fit for consumption according to the provisions in the Torah); and 2) the existence of a mechanism for annulling and voiding the vow by alternative payment of ransom to the Temple treasury, in which case the high priest, Pinchas, could have absolved Jephta from further obligation. The Midrash further proposes that because of Jephta’s pride-driven perceptions of protocol vis-á-vis his own quasi-monarchial status, he was loath to seek absolution from Pinchas, whereas Pinchas felt it beneath his dignity and position to make the initial approach to someone so ignorant as Jephta—almost a classical case of temporal-religious rivalry. In that Midrash, both are thus held responsible for the daughter’s sacrifice. And in the same interpretation, Jephta’s chief sin was ignorance. One opinion in that discussion further holds that even monetary absolution would have been unnecessary, since the vow was ipso facto already void by virtue of its illegitimate nature.

Medieval commentators were also careful to point out that Jephta’s vow was nonbinding precisely because, owing to its vague and confusing formulation, it allowed for just such a possible unintended and illegal result. Some (Ibn Ezra and the Radak, for example) determined that she was in fact not killed, although Nachmanides was critical of their denial. In a post-Talmudic alternative scenario now often accepted as one possible reading, Jephta spares his daughter’s life and condemns her instead to remain forever celibate in an ascetic, consecrated existence—a “sacrifice” of a normal, fulfilled life. Support for that view is found in the reference (Judges 11:37) to her virginity, and the words “and she did not know a man” are interpreted to mean that she “remained a virgin”—a state that in that era would have been considered tantamount to a forfeited life.

Later, more radical biblical criticism sometimes viewed the story as an etiological narrative, conceived after the fact to assign an origin to the annual women’s lamentation ritual. Other, more traditionally oriented scholars have continued to accept some degree of historicity for Jephta himself, while finding different origins for various parts of the story.

The prevailing modern interpretation, whose roots are still discernible in Talmudic as well as medieval comments, focuses on the danger of hasty vows and the consequences of such imprudence, rather than on the sacrifice itself. In his seminal study of the Jephta incident, David Marcus, while admitting his preference for the nonsacrificial conclusion, allows for both possibilities and objectively presents the arguments for each position. But he frames his entire consideration within a broader understanding of the story as essentially not about the sacrifice, but about the vow and its rashness. In a perceptive response to the ambiguity of the biblical wording, he posits the suggestion that the very ambiguity concerning the conclusion may well have been a deliberate literary or rhetorical narrative device.

The Jephta story has intrigued many Christian as well as Jewish authors, playwrights, poets, painters, artisans, tapestry makers, and composers from the late 17th century on. The many literary works include a Yiddish play by Sholem Asch (Yiftakhs tokhter, 1914), a Yiddish novel by Saul Saphire (Yiftakh un zein tokhter, 1937), and Ludwig Robert’s Die Tochter Jephtas (1813), the first German production of a stage play by a Jew.

In the musical realm there have been more than one hundred works based on the Jephta theme—including cantatas, oratorios, operas, choral pieces, instrumental portrayals, and arts songs. The most widely familiar treatment is probably Handel’s oratorio Jephtha (1752), on a libretto by Thomas Morell, who also collaborated with Handel on the oratorios Joshua (1748) and Judas Maccabaeus (1747), among others. Handel’s Jephtha concludes with an angel, not a high priest, adjudicating the dilemma and declaring that Jephta’s daughter is to be “dedicated to God” not by death, but by remaining in a virgin state—perhaps superimposing a Christian perspective.

Jephta’s Gelübde (Jephta’s Vow, 1812) was the first opera by the renowned German-Jewish composer Giacomo [Jacob Leibmann Beer] Meyerbeer, who later became one of the reigning composers at the Paris Opera and is today best known for his large-scale French operas of the mid-19th century. Jephta’s Gelübde was a one-act, three-scene collaboration with librettist/playwright Alois [Aloys] Schreiber, who gave the story the basically “happy” conclusion that the Talmud suggests could have been an alternative outcome had Jephta and Pinchas acted differently: the high priest releases Jephta from his vow. Produced in Munich, this work was considered by some more oratorio than opera, and it remains in manuscript.

Other well-known composers who have addressed the Jephta story include Robert Schumann, Lazare Saminsky, Vitali, Feruccio Busoni, Giovanni Paisiello, Mordecai Seter, Cimarosa, and Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, whose Bat yiftaḥ is considered the first opera to have been composed in Palestine. Many less widely known and even obscure composers fill out the list.

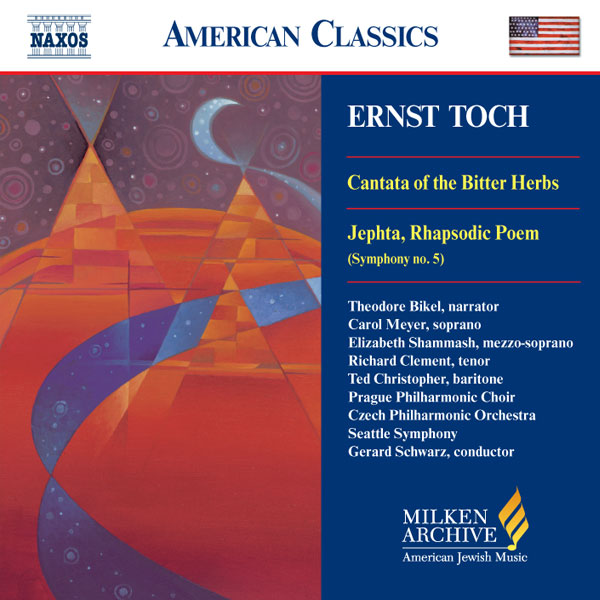

Toch never did write his intended opera on the Jephta story, but he completed the fifth symphony in 1963. It was premiered the following year in Boston by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Erich Leinsdorf. One inventive feature involves its use of four solo violins in prominent solo passages, which increase at one point to six. Brief lyrical sections alternate effectively with more brisk dramatic ones, and there is an overall theatrical sense. Among the critics who reviewed the premiere, two of them independently discerned Mahler’s influence in various elements of this symphony.

When queried about the symphony’s formal structure, Toch replied that he could not account for it: “The form to be achieved is inherent in the musical substance, following the law of its motive intent and becoming identical with it.”

Credits

Composer: Ernst TochPerformers: Gerard Schwarz, Conductor; Seattle Symphony

Publisher: G. Schirmer; Music Sales